Learning beyond the curriculum can close the attainment gap and improve university access, but it’s getting tougher to do this when the cost of living is so high.

Author: Dr Charlotte Hallahan, Senior Policy and Communications Officer

We’ve known for many years that The Scholars Programme increases applications and progression to competitive universities by building academic self-efficacy, which is a student’s belief that they can succeed at university. Now, new research has also shown a positive link between The Scholars Programme and attainment. At a time when schools, universities and parents are making difficult choices on where to spend ever tightening resources, we make the case for why learning beyond the curriculum can bring multiple benefits that support students, both in their more immediate education needs, and their longer-term outcomes.

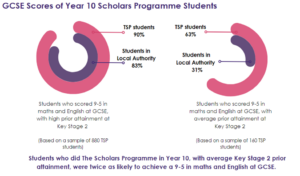

The Scholars Programme gives students from non-selective state schools and colleges the opportunity to work with a PhD researcher to experience university-style learning. It helps students to develop the university knowledge, academic skills, and attainment to secure a place at a competitive university. Recent data shows that Scholars Programme students have higher GCSE scores than Local Authority students who have similar Key Stage 2 prior attainment.

In the graphic below, you can see that students with average prior attainment were twice as likely to achieve a 9-5 in maths and English at GCSE after taking part in The Scholars Programme in Year 10:

This new data complements what we already knew about The Scholars Programme’s impact on attainment-related outcomes, such as academic self-efficacy, critical thinking, subject knowledge, and written communication. It also affirms what our students say about the programme. One of our students from Peterborough, for example, said that they are ‘a lot more confident in [their] essay writing abilities’ after participating in the programme, and another said that The Scholars Programme ‘made [them] want to work harder and aim for a more ambitious choice in higher education’.

For teachers, the programme also provides students a balance between insight into future study options, and practical skills that will support their learning now. A teacher from Northamptonshire who ran the programme in their school, for example, tells us that The Scholars Programme ‘provides students with a fantastic opportunity and gives them an insight into university life, which for many of the students would’ve been completely off their radar prior to taking part. It provides students with the tools to become independent learners and question their own viewpoints, perhaps for the first time.’

These findings demonstrate that university access activities can have real value in raising academic achievement in schools. They suggest that schools can benefit in multiple ways from investing in interventions that look to expand students’ learning beyond the curriculum and contribute to closing the attainment gap.

Why is it important to close the attainment gap?

Last month, the Education Policy Institute released a new report which revealed that the disadvantage gap between the most and the least advantaged students in GCSE English and maths widened to 18.8 months in 2022 (up from 18.1 months in 2023). The gap is now at its largest since 2012. For persistently disadvantaged students, meaning students that are eligible for free school meals for 80 per cent or more of their school lives, the gap is 22.7 months. This means that students from low-income families are almost a whole two years behind their peers.

Not only are we back where we were a decade ago, the EPI are forecasting that at the current rate of progress it may take another ten years to simply return the attainment gap to the level it was in 2019. These statistics are sad but not surprising. Many schools, universities, and charities have been working hard to combat this attainment gap (which was particularly acute during the coronavirus pandemic), but it’s clear that this attainment gap continues to widen.

GCSE attainment is a crucial indicator of a young person’s educational outcomes: the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that the better someone scores at GCSE, the more likely they are to hold advanced qualifications, and that it is ‘extremely unlikely’ for someone in the bottom fifth of GCSE scores to earn a university degree by their mid-20s.

Attainment is the biggest barrier to university access, so investing in programmes that can support attainment and increase university access can play a significant role in opening up a variety of opportunities for young people.

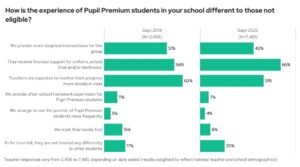

Raising attainment in the cost-of-living crisis

However, whilst the value in investing in this type of support is clear, it’s also not easy to do so. The cost-of-living crisis is continuing to impact everyone, with universities, families, and schools narrowing their budgets and cutting down on everything but the essentials. Teacher Tapp research from September 2023 showed that only 43% of their surveyed teachers answer ‘yes’ to the statement ‘we provide [specifically] targeted interventions for [Pupil Premium-eligible students]’, compared to 51% in Instead, schools have increased their financial support for Pupil Premium-eligible students and their families, including providing money for books, school trips, and school uniforms.

Credit: Teacher Tapp

While the need for attainment focused support is increasing, schools are less likely to spend their Pupil Premium budgets on targeted support, and more likely to spend it on essential school supplies. School leaders are making tough decisions between supporting students’ immediate and long-term needs.

Geography also plays a role here too. We can see regional differences coming through in the attainment gap: while the disparity in educational achievement between less advantaged students and their more advantaged peers exists across the entire nation, it is most pronounced in areas of high deprivation. In 2022, the South West had the largest attainment gap in the country at the end of secondary school, and in Wales the attainment gap has been consistently larger than the gap in England since attainment was first recorded by the Education Policy Institute in 2012.

What should we do about it?

Now, more than ever, it is important that Pupil Premium and Pupil Deprivation Grant funding, in England and Wales respectively, is at the appropriate level for schools to run these life-changing activities in their schools, and that policymakers ensure that it is protected in the years to come. With rising costs affecting every facet of our sector, the highest price we could pay is the opportunity to close the attainment gap. We must make sure that, even when budgets tighten, we continue to support and advocate for students to access programmes that boost their attainment and support them to make informed choices about their futures.

We can also share where different interventions are working, and where there’s still more to learn. We recently collaborated with TASO to create a multi-scale questionnaire that can be used to evaluate outreach activities across widening participation and student success teams. The more we share with each other, the more we’re able to support schools, universities and parents make those all-important decisions about how best to support students to access and succeed at university.

School, university, policy maker? Get in touch to discuss working with us: hello@thebrilliantclub.org