Authored by Hannah Thomson (Research and Evaluation Officer) and Dr Lauren Bellaera (Research and Impact Director)

Focusing in on post-qualification admissions

In January 2021, the UK Government launched a consultation to seek views on whether to change the current system of higher education admissions and move to a system of post-qualification admissions (PQA) in England, Scotland, and Wales.

Under the current model, students apply to university, receive offers, and select where they would like to go before receiving their A-level results:

A PQA system could take several different forms. In Model 1, students apply to university and select where they would like to go after results day:

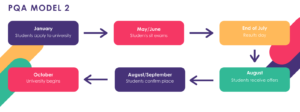

In Model 2, students apply to university before results day but receive and confirm their offers after receiving their A-level results:

The main difference between the current system and the proposed PQA models therefore lies in whether university applications and final decisions are made before or after results day, as well as the reliance on predicted versus actual grades.

Indeed, one of the biggest concerns with the current system, in which students apply to university with predicted grades based on teacher assessment and judgement, is that predicted grades can sometimes be inaccurate, and that disadvantaged students in particular are ‘undermatched’ in relation to the grades they actually achieve. However, data analysis in a recent HEPI blog presents a different view, suggesting that, for the most part, predicted grades do not disadvantage underrepresented groups.

Across the sector, schools, colleges, education providers, and universities are engaging with the consultation, acutely aware of the impact that this reform could have on students’ lives, especially at a time where there has already been significant disruption due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

At The Brilliant Club, we are also considering this reform carefully, and as a national university access charity whose sole mission is to increase the number of young people from underrepresented backgrounds progressing to highly-selective universities, it matters to us that we hear the voices of the students that this reform will directly affect.

Throughout April 2021, we ran a series of semi-structured focus groups with 29 Year 12 students and 4 university students in England, to gather their opinions on PQA. In this blog, we share their anonymous thoughts and reflections about the proposed education reform.

What do students think of PQA?

Concerns over post-qualification applications: The majority of Year 12 students and university students that we spoke to agreed that a system of post-qualification applications and offers should be avoided (Model 1). Under this system, results day would be earlier in July and students would apply afterwards. The primary argument against this system was that it would condense the university application and decision-making process into a short window of time, as students would have to research their options, apply, receive offers, and respond to those offers in the space of about two months in August and September. This raised concerns for students in terms of the logistical challenge of securing accommodation, transport, and buying materials for university:

“it wouldn’t be enough time for students to fully research if the university and the course is good enough for them […] I think logistically it’s quite difficult for universities and for students […] I feel it would cause stress on both sides.” (Year 12 student)

While students generally concluded they would be willing to come back to school during the summer for a week or so to attend university application workshops, they noted that this may not be the case for all students and that it would disrupt teachers’ summer breaks. Further, the Year 12 students did not think this would give universities enough time to fairly consider each application, particularly if interviews or auditions were involved. They were keen that the content of their applications should not be sacrificed in order for universities to process them faster.

“It will be hard for universities to confirm places and do all of the stuff in one months’ time.” (Year 12 student)

However, a minority of students did favour a PQA system (Model 1), as applying with final grades would alleviate some of the uncertainty caused by predicted grades:

“When applying after you’ve got your grades it [can]make you feel more secure 100% […] whereas in the current system you are hanging in the balance.” (Year 12 student)

Year 12 students were mostly in favour of post–qualification offers: The system of post-qualification offers but pre-qualification applications was considered more appealing (Model 2), with the majority of Year 12 students favouring this system over the current application process. This reflects the findings from UCAS’ engagement with university students, where over 70% said they would prefer to apply to university before sitting exams and receiving their results. Under this model, students would apply to university at a similar time as they currently do, but results day would be moved forward to July and students would receive offers and confirm their places after receiving their A-level results:

“I think applying before is the better of the two models, but I think getting your offer after your results is way better.” (Year 12 student)

A major benefit of post-qualification offers is that students could still receive the same level of application support from school over the course of Year 12 and 13, which they valued highly:

“Having the support of teachers and also having conversations with friends whilst you’re in school is crucial.” (Year 12 student)

All the students that took part in the focus groups thought personal statements were a positive feature of the university applications, as the writing process helped them to figure out whether they were applying for the right course. Further, it allowed them to convey their personalities and motivations to a university and not be solely assessed on their grades:

“You can get more of a sense of someone and how they think beyond just their academic credentials.” (Year 12 student)

University students were in favour of the current system: Whilst the university students agreed that Model 2 was preferable to Model 1 if PQA were to go ahead, given a choice, they were unanimously in favour of keeping the current system but improving the way predicted grades are produced, e.g. by bringing back AS levels. Two university students found that having predicted grades was useful, as they were predicted higher grades than they achieved but still ended up at their first-choice university. The students felt that having predicted grades and receiving an offer on that basis allowed them to develop a relationship with the university, which helped them progress to that university. Finally, the students noted that predicted grades became less relevant once they had received their university offers, as this is what they ended up working towards during their A-levels. As one student summarised:

“I think predicted grades are really really useful, but I think the system that they are based on needs work.” (University student)

Year 12 students’ views on predicted grades: Relative to the university students, Year 12 students felt more strongly that predicted grades were unfair – receiving underpredicted grades could restrict the universities students can apply to, but receiving overpredicted grades could lead to disappointment on results day:

“Predicted grades leave a lot of uncertainty.” (Year 12 student)

The requirement to move learning online during the pandemic and the impact this could have on predicted grades was of concern to students at one school, as they were concerned that a reduction in in-person interactions might make it more challenging for teachers to make predictions. On the flipside, one student noted that higher predicted grades would motivate her to work harder. Overall, students felt that the effect of predicted grades on motivation and stress levels depends on the individual, and students from two schools suggested that predicted grades could be improved by introducing more frequent lower-stakes assessment through Year 12, and students from one school suggesting something like modular grades as a solution.

Added to this is the often-misunderstood nature of predicted grades, which are set by teachers to reflect the highest grades a student might realistically achieve to open up more universities for them to apply for, rather than what they expect the student to receive in their exams. As a teacher present in one of the focus groups noted, their school avoids the term ‘predicted grades’ and instead refers to ‘reference grades’ to provide greater transparency to students about their purpose. If predicted grades continue to exist, it is vital that their purpose is clearly messaged to teachers and students.

Predicted grades are not the (only) issue

A stand-out conclusion from the focus groups is that students raised many more issues besides predicted grades. One is how they are assessed in Year 12 and 13, with multiple students preferring a system involving more frequent assessments to base their predicted grades on, and the university students favouring the reintroduction of AS levels.

The issues around the current clearing process were raised by a university student. Clearing runs from July to October but is most frequently accessed by students after results day if they meet none of their university offers, as it enables them to take university places that have not yet been filled. However, this is often done by phoning university hotlines to check whether you meet their entry requirements without much opportunity for planning. A university student highlighted the time pressure involved in clearing:

“You are under a time limit, the offer is also under a time limit, and that doesn’t help because you don’t get to think about it.” (University student)

The student also had concerns about the lack of information and support she was given about clearing at school, which was reflected by the other university students:

“No one really told us anything, even on the UCAS website there wasn’t much information.” (University student)

At one school, students frequently referred to the underlying issue of reforming university admissions – that even a PQA system could not guarantee getting rid of inequalities:

“people from deprived areas […] might not have people pushing them to achieve.” (Year 12 student)

Furthermore, the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic on Year 12 students could not be ignored, with participants reflecting that the reduced time spent in school actually gave them more time to think about their options, although lockdown measures limited prospects for work experience and gap years. Opinions on whether now is the right time to introduce admissions reforms given the disruptions students have already faced were mixed – some felt it is now or never, and others did not want to be faced with even more uncertainty.

Reflections

Consulting the students at the heart of educational reform is beneficial both for the students and for us as researchers, educators, and policymakers. Their insightful contributions raised important issues relevant to the debate and empowered the students to feel a part of the important decisions that will affect them.

Running the focus groups with Year 12 students and university students enabled us to gather different perspectives on university admissions. Year 12 students are at the beginning of their higher education journeys, whilst university students could reflect on their experiences in hindsight. It should also be acknowledged that due to the number of students that took part in the focus groups, school students’ views were more represented in the findings compared to university students; 29 vs. 4 students, respectively.

To summarise, the issues around predicted grades are clear to us and to students, however moving to a full PQA system (as outlined in Model 1) where students apply to university, receive offers, and decide where to go after results day, is both logistically challenging and may create more problems than it solves.

Central to this view is the application support provided to students by teachers, and the benefits of having a longer time span of preparing an application during Year 12 and 13 rather than a few weeks in the summer. However, if predicted grades are to remain in place, it is worth considering which kind of assessments they are determined by and how their role is messaged to students. A more productive solution to the PQA debate may be to build on the system that we already have – a view which is also shared by some teachers. Whatever the solution, it is important that student voices are heard and consulted as they are the ones who will be affected by the changes that do or do not happen.

Many thanks to the university students at Imperial College London, Queen Mary University of London, University of Kent, and University of Southampton, and to staff and students at Holmleigh Park High School, London Academy of Excellence Tottenham, Saffron Walden County High School, and St Thomas the Apostle College for taking part in this research project. The views stated in this blog reflect those of the focus group participants and not their associated institutions.